Kaiser Family Foundation Washington Post Rural Urban Divide

Download

Authors: ; Ilyin, Ilya V.; Korotayev, Andrey

Almanac: Globalistics and Globalization Studies Global Development, Historical Globalistics and Globalization Studies

The paper focuses on the catamenia of increasing and intensified growth of urbani-zation in the nineteenth century. That was the origin of the modernistic urbanized world. The authors emphasize, however, that in the nineteenth century urbanization was initially vibrant in Europe and the U.s.a.. In other world regions rapid urbanization started generally in the twentieth century and led to a tremendous increase of the world urban population from less than 200 meg in 1900 to 2.86 billion in 2000.

Keywords: urbanization, cities, Europe, the nineteenth century.

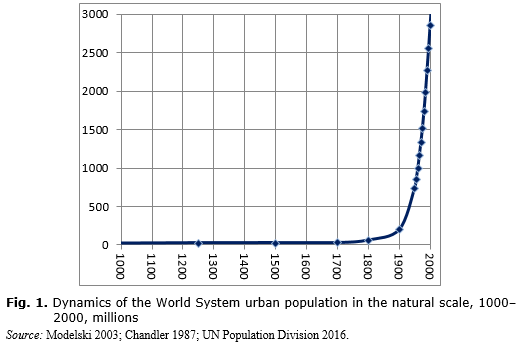

To offset with, let us consider the dynamics of urbanization in the nineteenth century in a broader, millennial perspective (meet Fig. 1).

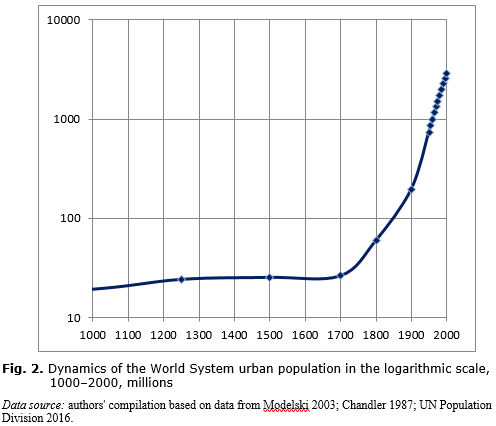

Looking at Fig. 1, ane could get the impression that urbanization occurred in the twentieth rather than in the nineteenth century. Indeed, an explosion-like growth of urban population was observed in the twentieth century. Nonetheless, a closer wait at the aforementioned time bridge in logarithmic scale makes information technology articulate that the previous trend of urban population dynamics started changing already in the eighteenth century. The nineteenth century and then brought about such rates of urbanization growth as were previously unknown (see Fig. 2).

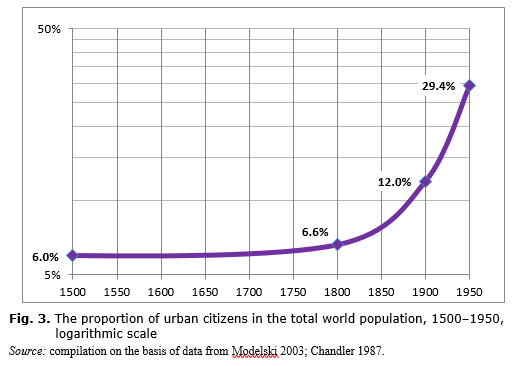

The meaning of the nineteenth century in the history of urbanization becomes even more pronounced when one does not look at the absolute number of urban citizens but rather at their proportion in the total world population, i.e. the urbanization level (see Fig. 3).

The nineteenth century witnessed a dramatic change in the dynamic of urbanization. Even though the early on mod time brought most numerous social, political, and economical changes, leading to the emergence of modern-type states, there was only little change of patterns of urbanization if compared with previous centuries. The number of urban dwellers was growing, but this growth ran parallel to the full general population growth, and so their proportion in the full population remained virtually stable. Thus, in Europe the share of urban population (for cities with population of 5,000 and more) increased only from ten–11.five per cent in 1500 to 12–thirteen per cent in 1700 (Bairoch 1988: 176). According to somewhat lower estimates the level of European urbanization in 1800 was only 10 per cent(de Vries 1984: 45).

In other regions of the globe the situation was pretty much the same, with urbanization levels being approximately the same equally or even lower than in Europe. In China with its rich history of urban civilization simply six–7.5 per cent of the population resided in cities (population exceeding 5,000 people) in the early nineteenth century (Bairoch 1988: 358). In Nihon about 11–xiv per cent of population dwelled in cities in 1700 (Ibid.: 360).

The nineteenth century broke this long-term stability, every bit the share of world urban population doubled from 6.six per cent in 1800 to 12 per cent in 1900. The growth of urban population significantly outpaced the growth of the globe population in full general. This allows us to land that it was namely in the nineteenth century that the modern process of global urbanization began.

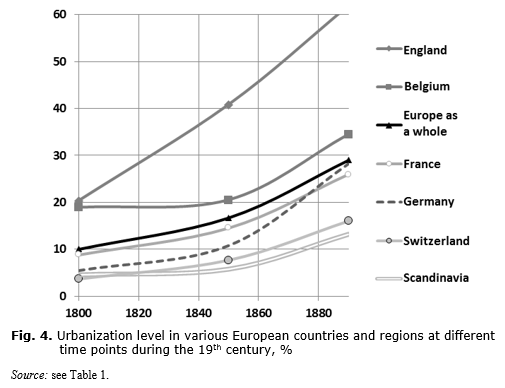

However, despite its crucial influence on various spheres of life, the pace of the urban population growth in the nineteenth century should not exist exaggerated. It was specially fast in Western Europe, but even here only ane land, Britain, was more or less close to completing the urban transition by the end of the nineteenth century – more than than half of its population resided in cities by 1900. Meanwhile, other European countries had only passed the initial stages of the urbanization procedure; fifty-fifty the leaders, such as Kingdom of belgium and the netherlands, had only well-nigh ane-tertiary of their population dwelling in cities by 1890 (see Tabular array ane and Fig. 4).

Table 1. The share of urban population in diverse European countries and regions at dissimilar time points during the 19th century, %

| Country/region | 1800 | 1850 | 1890 |

| England | 20.3 | 40.eight | 61.ix |

| Kingdom of belgium | 18.nine | 20.v | 34.5 |

| Federal republic of germany | 5.5 | 10.8 | 28.2 |

| France | eight.eight | fourteen.5 | 25.nine |

| Spain | 11.1 | 17.3 | 26.8 |

| Italian republic | 14.6 | 20.iii | 21.two |

| The Netherlands | 28.8 | 29.5 | 33.4 |

| Portugal | 8.7 | xiii.2 | 12.7 |

| Scandinavia | 4.six | 5.8 | 13.2 |

| Switzerland | 3.vii | vii.7 | 16.0 |

| Total Europe | ten | xvi.7 | 29.0 |

Source: de Vries 1984: 45–46.

Later 1890 European urbanization accelerated remarkably, and by 1910 the proportion of urban citizens in European population increased to 41 per cent. This was happening against the backdrop of a huge dispatch in the full general growth of the population in Europe. As a result of these two processes acting together, the overall growth of the absolute numbers of metropolis dwellers was truly amazing – afterward only a little more than 100 years the urban center population of Europe rocketed from 19 million to 127 1000000 (Bairoch 1988: 217).

This growth was concentrated in big cities and particularly the capitals. 'The reward of size meant growing economical opportunity in the metropolis, specially if it was likewise the seat of government, where the concentration of labor, entrepreneurship, commerce, credit, and intelligence attracted the restless and ambitious from all classes of society' (Hamerow 1989: 94–95). However, not infrequently the capitals were outpaced by centers of industry and trade in attracting new citizens.

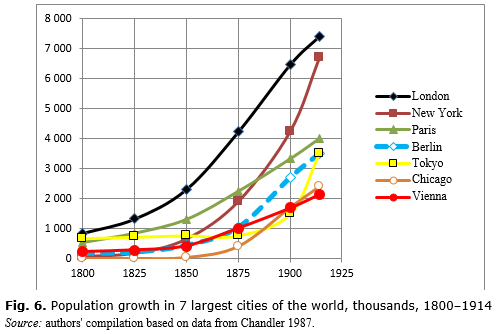

In the nineteenth century, large cities were growing all over the world. Even so, it was in Europe and in the United states of america that this growth was particularly pronounced (see Tabular array 2). As a result of this, Europe and the USA greatly outpaced other world regions in terms of urbanization, and we run across a major reconfiguration of the global distribution of the globe largest cities. This phenomenon is conspicuously visible when comparing the list of 30 largest cities of the world in 1800 with that in 1914 (see Table 3).

Table ii. Accented (thousands) and relative (%) population growth in 1800–1914 in xxx largest (as of 1914) cities of the earth

| | City | Accented population growth during the | Relative population growth during the nineteen thursday century, % (population in 1800 = 100 %) |

| 1. | London | half dozen,558 | 762 |

| 2. | New York | vi,637 | 10,535 |

| 3. | Paris | 3,453 | 631 |

| 4. | Berlin | 3,328 | 1,935 |

| 5. | Tokyo | ii,815 | 411 |

| six. | Chicago | 2,420 | Established afterwards 1800 |

| 7. | Vienna | 1,918 | 830 |

| 8. | Saint-Petersburg | 1,913 | 870 |

| nine. | Moscow | i,557 | 628 |

| ten. | Philadelphia | ane,692 | ii,488 |

| 11. | Buenos Aires | 1,596 | 4,694 |

| 12. | Manchester | 1,519 | 1,875 |

| 13. | Birmingham | ane,429 | 2,013 |

| 14. | Osaka | 1,097 | 286 |

| xv. | Calcutta | 1,238 | 764 |

| 16. | Boston | ane,269 | 3,626 |

| 17. | Liverpool | ane,224 | one,611 |

| eighteen. | Hamburg | ane,183 | one,011 |

| xix. | Glasgow | 1,041 | 1,239 |

| 20. | Constantinople | 555 | 97 |

| 21. | Rio de Janeiro | ane,046 | 2,377 |

| 22. | Mumbai | 940 | 671 |

| 23. | Budapest | 996 | 1844 |

| 24. | Beijing | –100 | –9 |

| 25. | Shanghai | 910 | 1011 |

| | City | Accented population growth during the | Relative population growth during the xix thursday century, % (population in 1800 = 100 %) |

| 26. | Warsaw | 831 | 1108 |

| 27. | St. Louis | 804 | 2 |

| 28. | Tianjin | 655 | 504 |

| 29. | Pittsburgh | 774 | 51567 |

| xxx. | Cairo | 649 | 295 |

Source: Chandler 1987.

Tabular array 3. 30 largest cities of the world in 1800 and in 1914 (cities of Europe and the The states are printed in assuming type)

| 1800 | 1914 | ||||

| City | Country | Population in 1800, thousands | City | Country | Population in 1914, thousands |

| Beijing | China | 1,100 | London | Great Uk | 7,419 |

| London | United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland | 861 | New York | the USA | half-dozen,700 |

| Canton | Communist china | 800 | Paris | France | 4,000 |

| Edo | Nippon | 685 | Berlin | Germany | 3,500 |

| Constantinople | the Ottoman Empire | 570 | Tokyo | Japan | 3,500 |

| Paris | France | 547 | Chicago | the U.s.a. | 2,420 |

| Naples | Kingdom of Naples | 430 | Vienna | Austria | 2,149 |

| Hangzhou | People's republic of china | 387 | Saint-Petersburg | Russia | ii,133 |

| Osaka | Japan | 383 | Moscow | Russian federation | 1,805 |

| Kyoto | Japan | 377 | Philadelphia | the Usa | 1,760 |

| Moscow | Russia | 248 | Buenos Aires | Argentina | ane,630 |

| Suzhou | China | 243 | Manchester | Nifty Britain | one,600 |

| Lucknow | India (Bang-up United kingdom) | 240 | Birmingham | United kingdom | one,500 |

| Lisbon | Portugal | 237 | Osaka | Nippon | 1,480 |

| Vienna | Republic of austria | 231 | Calcutta | India | 1,400 |

| Xian | China | 224 | Boston | the The states | 1,304 |

| Saint-Petersburg | Russia | 220 | Liverpool | Great Great britain | 1,300 |

| Amsterdam | Netherlands | 195 | Hamburg | Frg | ane,300 |

| Seoul | Korea | 194 | Glasgow | U.k. | 1,125 |

| Murshidabad | India (Smashing Britain) | 190 | Constantinople | the Ottoman Empire | 1,125 |

| Cairo | Arab republic of egypt | 186 | Rio de Janeiro | Brazil | ane,090 |

| Madrid | Spain | 182 | Bombay | Bharat | ane,080 |

| Benares | India (Swell United kingdom) | 179 | Budapest | Hungary | 1,050 |

| Amarapura | Burma | 175 | Beijing | China | i,000 |

| Hyderabad | India (United kingdom) | 175 | Shanghai | People's republic of china | 1,000 |

| Berlin | Federal republic of germany | 172 | Warsaw | Poland | 906 |

| Patna | India (U.k.) | 170 | St. Louis | the The states | 804 |

| Dublin | Republic of ireland | 165 | Tianjin | China | 785 |

| Kintechen | China | 164 | Pittsburgh | the USA | 775 |

| Calcutta | India (Slap-up United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland) | 162 | Cairo | Arab republic of egypt | 735 |

Source: Chandler 1987.

While in 1800 but three out of the world'southward 10 largest cities were located in Europe, in 1914 nine out of 10 largest cities belonged to the European region or the USA. The only exception, Tokyo, supports the full general rule, as Japan was the nearly successful case of the European-style modernization outside the European globe.

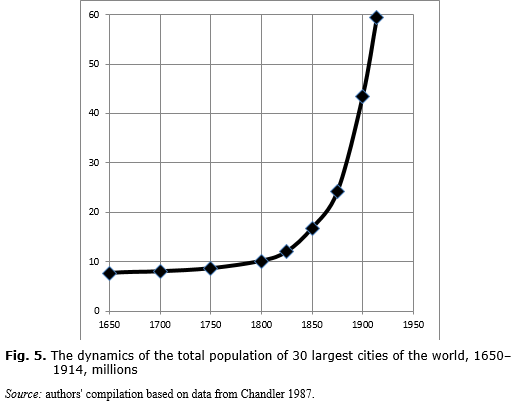

The dynamics of the total population of the xxx largest cities of the world betwixt 1800 and 1914 was explosion-similar (see Fig. five). Data on the population growth in the 7 largest cities of the earth in 1800–1914 are presented in Fig. 6.

The Emergence of Modern-Type Cities

Sanitary infrastructure. For much of the nineteenth century the decease rates in urban areas remained extremely high, especially considering babe and child mortality. For case, in British industrial cities of Lancashire and Cheshire 198 out of one,000 children died before their commencement birthday – twice more than in rural areas (Bairoch 1988: 67). In the French city of Lille, one-quarter of children died before the age of three years (Lees and Lees 2007: 143). A similar state of affairs had been observed in many other industrial cities in Europe. The main reasons for high bloodshed were dirty and unsanitary atmospheric condition in the streets and houses (especially in the poor working-class neighborhoods), and even the contamination of the air of industrial cities was unbearable (Schultz 1989: 112). Gradually, in the second one-half of the nineteenth century, diverse solutions were offered to the problems of urban sanitation infrastructure. Thus, individual wells by central public water supply. Past the end of the nineteenth century more than 40 of the 50 largest US cities had extensive water systems created and maintained by the state (Schultz 1989: 164). Previous ways of waste product disposal (part of it was taken by farmers for fertilizing, but a pregnant portion was tending of in a completely unsanitary manner – eastward.yard., dumped and poured in the outskirts of the city) were overtaken past modern sewerage systems. These two phenomena (along with street paving, improvement of public lighting, etc.) played a crucial part in the development of cities and the decline of urban mortality.

Public transportation. Cities with hundreds of thousands citizens were confronted with the problem of organizing a ship network. Indeed, in contrast to the medieval craftsmen, industrial workers lived and worked in different places, so almost of them had to commute every twenty-four hours. According to Paul Bairoch, the public transport organization was born in 1828 in Paris (which then counted more than than 800,000 people) when the city installed its first passenger vehicle line. From Paris the public send arrangement spread throughout the Western world. Already in 1829, inspired past the success of Paris, London followed its example, and in 1831 New York did the same. In the next two decades the public transport organisation appeared in almost all the major cities in Europe and N America. Public transport rapidly gained popularity. By the end of the 1850s omnibuses in London and Paris carried 40 one thousand thousand passengers annually (Bairoch 1988: 281; Clark 2009: 273). In the 1850s the rail urban transport began to actively expand. The first electric tram was demonstrated by Siemens in 1879 and started working in Frankfurt in 1881. Electrification contributed to the development of the underground urban send – on the eve of the Offset World War metro lines were functioning in 12 cities of the world, such as London (since 1863), New York (1868), Istanbul (1875), Budapest (1897), Glasgow (1897), Vienna (1898), Paris (1900), Boston (1901), Berlin (1902), Philadelphia (1907) Hamburg (1912), Buenos Aires (1913) (Bairoch 1988: 282).

Urban infrastructure. An important novelty of the nineteenth century was the idea of planning the urban landscape. The initiative belonged to Prussia where in 1808 each municipality was obliged to found a edifice commission, responsible for street paving and drainage systems, also as for the condition of sidewalks (Lees and Lees 2007: 123).

An integral part of the modern cities was constituted by numerous shops, especially large section stores, many of which (Le Bon Marché, the outset department store, which opened in Paris in 1852, London'due south Selfridge, etc.) continue to operate today. Nigh every major Western European city (as well every bit many small towns) for a certain menstruum of the nineteenth century experienced a real boom in the opening of stores. For example, in Great britain their number grew by 300 per cent in the first one-half of the nineteenth century. In Vienna the number of stores tripled in 1870–1902, while in Paris it increased eightfold (Clark 2009: 266).

Pregnant changes were taking place not only in the public infinite of cities, but besides in individual homes. By the center of the nineteenth century rich American and European homes had running water; afterwards this innovation appeared in the houses of the center course. 93 percent of London houses had running water on the eve of the First Earth War (Clark 2009: 272). A change in house planning implied a dissever room for hygiene procedures, which undoubtedly contributed to the reject in mortality from infectious diseases (Schultz 1989: 164).

References

Bairoch, P. 1988. Cities and Economic Development. From the Dawn of History to the Present. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Chandler, T. 1987. 4 Thou Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press.

Clark, P. 2009. European Cities and Towns: 400–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Printing.

Hamerow, T. D. 1989. The Birth of a New Europe. Land and Society in the Nineteenth Century. Chapel Hill and London: The Academy of Due north Carolina Press.

Lees, A., and Lees, L. H. 2007. Cities and the Making of Modernistic Europe, 1750–1914. New York: Cambridge University Printing.

Modelski, G. 2003. World Cities: –3000 to 2000. Washington: FAROS 2000.

Schultz, S. One thousand. 1989. Constructing Urban Culture: American Cities and Metropolis Planning, 1800 – 1920. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

UN Population Division. 2016. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Diplomacy. Population Sectionalisation Database. URL: http://www.united nations.org/esa/population.

Vries, J., de. 1984. European Urbanization 1500–1800. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Printing.

* This research has been supported by Russian Scientific discipline Foundation (project No 15-xviii-30063).

Source: https://www.SocioStudies.org/almanac/articles/the_nineteenth-century/

Post a Comment for "Kaiser Family Foundation Washington Post Rural Urban Divide"